Archives of Otolaryngology and Rhinology

The role of Allergy in Chronic Middle Ear Disease

Retired, Associate Clinical Instructor, Department of Otolaryngology, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Mass, USA

Author and article information

Cite this as

Hurst DS. The role of Allergy in Chronic Middle Ear Disease. Arch Otolaryngol Rhinold. 2025; 11(2): 019-025. Available from: 10.17352/2455-1759.000162

Copyright License

© 2025 Hurst DS. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Objective: OME is one of the most prevalent childhood diseases across the globe. OME is a disorder that most commonly begins in childhood but is seen in all ages and is the leading cause of hearing loss and speech difficulties, leading to impaired educational performance in children. This report will review the information that supports recent studies, which have shown that nearly 100% of OME patients are allergic and that when these allergies are properly treated, the patient’s effusion will resolve.

Methods: In order to characterize the relation of allergy or infection to OME, we measured ECP, MPO, and tryptase in effusion from 97 patients. Biopsies from both normal and diseased patients were taken from the promontory of their middle ear and stained for mast cells. All patients underwent allergy testing.

Results: Nearly all OME patients responded to immunotherapy.

Conclusion: This data introduces a paradigm shift in the approach to children presenting with OME requiring tubes, as nearly 100% of OME patients are allergic, and unlike the use of antibiotics, which only treat the current episode, when their allergies were properly treated with immunotherapy, the patient’s tendency to experience recurrent effusions all resolved.

AOM: Acute Otitis Media; OME: Otitis Media with Effusion; IDT: Intradermal Testing; SPT: Skin Prick Testing

Introduction

Recurrent middle ear infections have been a scourge of humanity for millennia, as they often bode chronic hearing loss or worse — mastoiditis that most often resulted in death. Major advances began with Astley Cooper’s pioneering operation of piercing the human membrane tympani as written up in the Royal Society’s publication, Philosophical Transactions, in 1801. Secretory otitis media (OM) was first described by Politzer in 1869. Observations as to its incidence, etiology, pathology, and therapy were reported with increased frequency through the 1950s and 1960s following the advent of antibiotics in the 1940s and the development of tympanostomy tubes by Shea in 1952.

Pediatricians have remained the “gatekeepers” for managing children with chronic OM. They often refer these children to otolaryngologists for surgical treatment, but remain their caretakers as they mature. Yet most of the literature regarding the “good, bad, and ugly” of tympanostomy tubes has largely remained outside their purview. This report hopes to update them on current observations as to the role of allergies as the prime cause of children’s chronic middle ear disease.

Materials and methods

Otitis media with effusion (OME) describes an inflammatory process within the middle-ear space that is generally associated with the accumulation of fluid within the middle ear space persisting for greater than 3 months. It is one of the most prevalent childhood diseases across the globe [1] and is the major form of chronic relapsing inflammatory disease of the middle ear [2].

OME leads to impaired educational performance in children, with 22.6% of cases occurring annually in children under age 8. Otitis media-related hearing impairment has a prevalence of 30.82 per 10,000. Each year, 21,000 people die due to complications of OM [3].

The diagnosis and treatment of chronic otitis media with effusion (OME) has been a long-standing conundrum in medical practices. Why? The medical literature dating back to 1931, as reported through 21 studies of 2326 patients by Proetz, Shambaugh, Zhang, Draper, Doyle, Pelikan, Ojala, McMahan, Tomonaga, Nsouli, Lasisi, Nguyen, Tian, Sobol, Smirnova, Shim, Smirnova, Luong, and Hurst [4] support the allergic cause of otitis media with effusion (OME) and that “ETD responds best to immunotherapy” (Table 1)[4].

Yet while hay fever, asthma, dermatitis, etc, respond to the traditional anti-allergic medicines and antihistamines, OME itself shows little benefit from these treatments. Persistence and/or recurrence of fluid in the middle ear leaves the surgeon to rely on repeated myringotomy and placement of tympanostomy tubes (M&T). Unfortunately, repeated M&T, as well as eustachian tube dilatation, do not address the underlying etiology.

We contend that the middle ear behaves like the rest of the respiratory tract and that what has been learned about the atopic response in the mucosa of the sinuses and lungs may be applied to the ear to help in our understanding of OME. Unfortunately, surgical approaches such as repeated M&T, as well as eustachian tube dilatation, do not address the underlying etiology. Identification of factors involved in the chronicity of otitis media is an essential step in the treatment and ultimate prevention of chronic disease.

Immunologic studies have confirmed OME to be an immune-mediated disease [3]. However, few otologists credit allergy with a direct role in the pathophysiology of middle ear disease, possibly due to the lack of instruction regarding allergic mechanisms during surgical training [5].

All the mediators necessary for a Th2 allergic response are present in the middle ear [2]. These include tryptase. Patients with OME are not only almost universally atopic, but their chronic middle ear disease will resolve with immunotherapy in over 85% of cases, which supports the hypothesis that the middle ear is a target of allergy.

Several critical questions require answers: ‘‘Why is it that 5- 10% of patients with acute otitis media progress to chronic OME despite adequate antimicrobial therapy? [5] Why do 20% of children require a second set of tympanostomy tubes or develop otorrhea”? [5] “Why, despite positive cultures, are antibiotics no more effective than a placebo in patients with cOME?” [5] “Why do patients with OME have 4 to 5 times the expected incidence of allergies? [6,7] Why is OME more typical of older children who have reached an age at which they would have been expected to have outgrown an immature ET morphology?’’ ‘‘To what degree then is allergy a risk factor"?

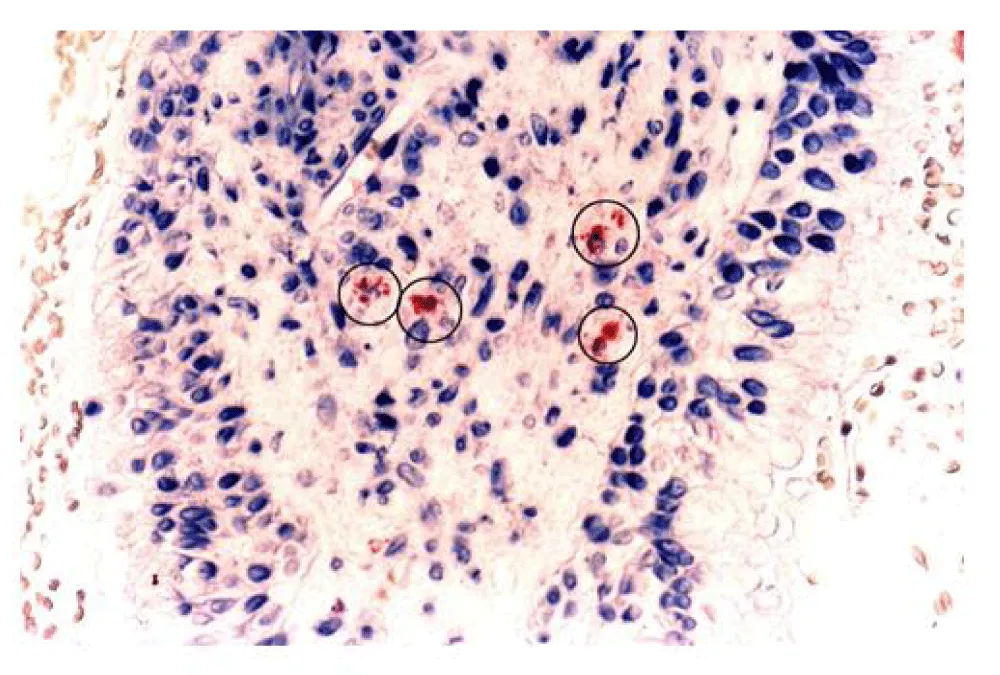

The short answer to these questions requires an understanding of the pathophysiology of the mucous membrane itself. The middle ear space is an anatomic extension of the upper airway by way of the ET, and because the middle ear is capable of mounting an inflammatory response similar to other areas of the respiratory tract, it has been proposed that the middle ear is part of the Unified Airways Concept [8]. The middle ear has been shown to have degranulating mast cells and eosinophils [9] just as in the sinuses.

Pathophysiology

Allergy or atopy, for current purposes, can be defined as a genetically transmitted, T-cell-mediated, cytokine-driven, eosinophil-affected inflammation. The relation of OME to allergy remains controversial. In order to understand the inflammatory processes that allow OME to persist, it is essential to characterize the cellular constituents and their degree of activity in the diseased middle ear. During the past 40 years, evaluation of middle ear effusion fluid has made astonishing advances in understanding what is occurring in the middle ear to cause the effusion. This report will summarize those advances.

Clinical studies have shown that patients with OME have allergies that can be diagnosed by standardized intradermal (IDT) or skin prick testing (SPT) or in vitro testing [4,9,10] When these allergies are properly treated, the patient’s effusion will resolve [10-13].

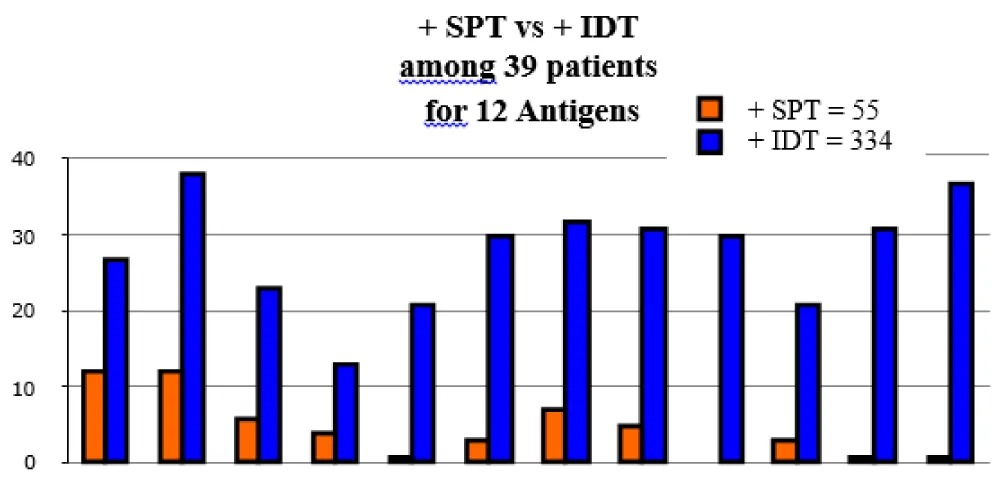

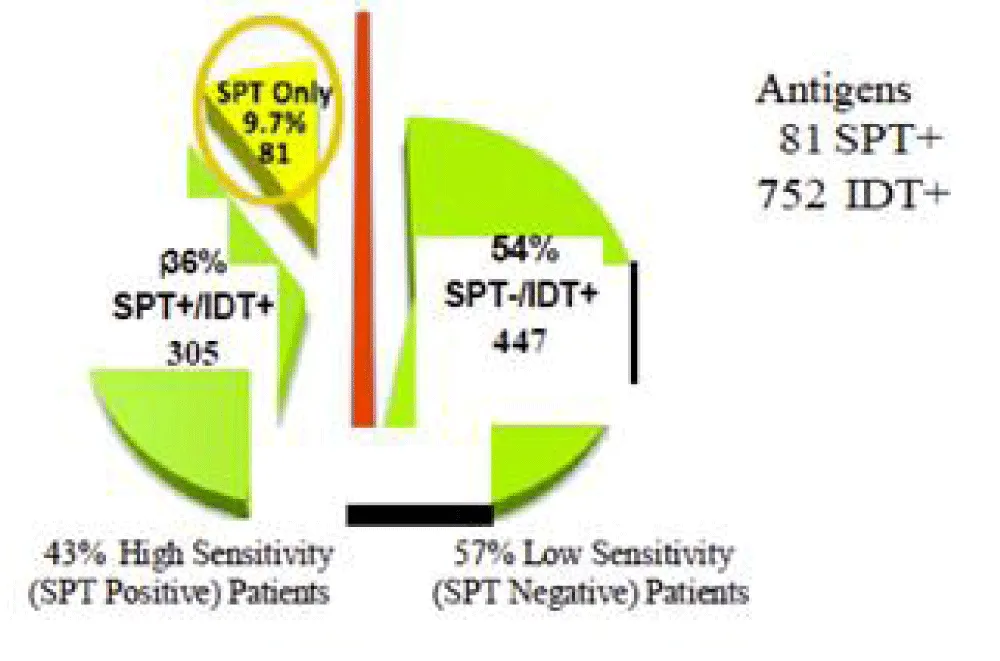

Adding IDT testing to SPT discovers 54% more allergens (Figures 1,2) [7,12]. Set found 81 antigens while IDT discovered 752 antigens. SPT plus IDT found 305 antigens (36%) as compared to set plus IDT found 447 antigens (54%).

Results

Finding both mast cells and their mediator tryptase in middle ear fluid confirmed that a Th2 driven immune response was present in a majority of ears that have chronic effusion. This supports the hypothesis that the middle ear mucosa is capable of an allergic response and that the inflammation within the middle ear of most OME patients is allergic in nature [6]. Thus confirming that the middle ear is part of the Unified Airways Concept [8].

Immunologic studies have confirmed OME to be an immune-mediated disease [9]. However, few otologists credit allergy with a direct role in the pathophysiology of middle ear disease, possibly due to the lack of instruction regarding allergic mechanisms during surgical training [9].

Clinical evidence

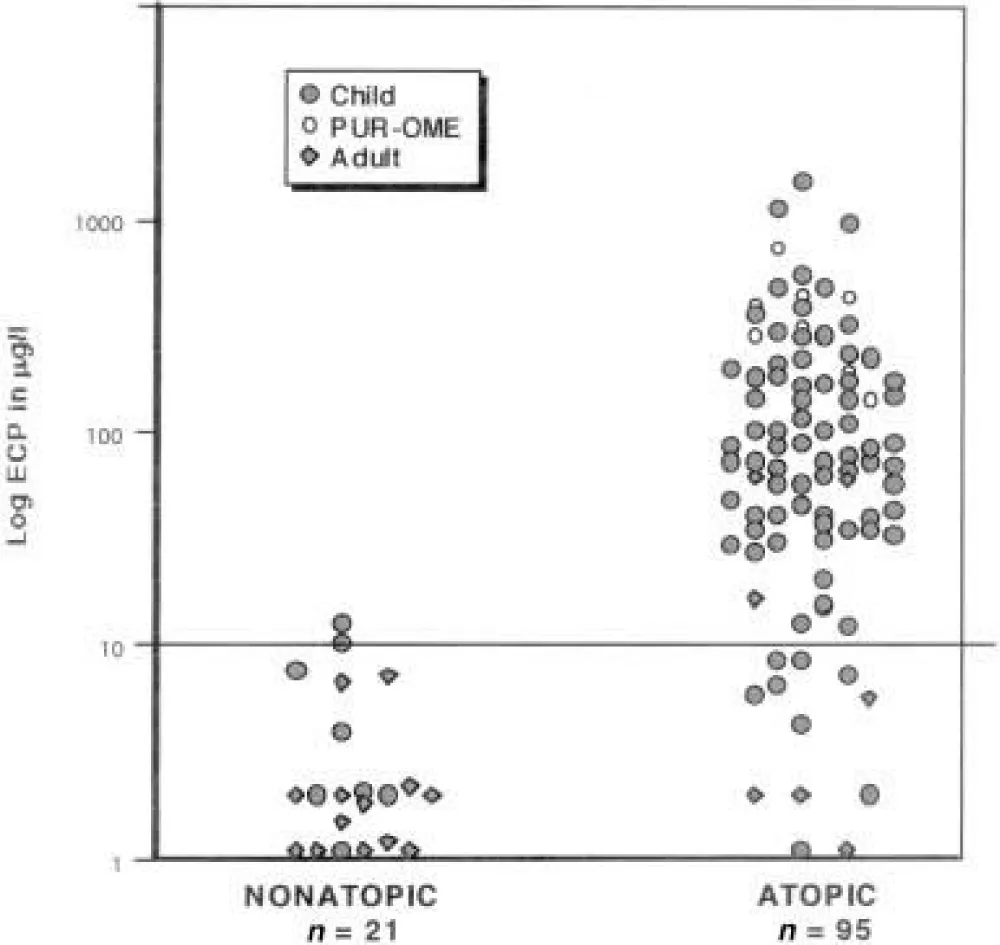

In order to characterize the relation of allergy or infection to OME, we measured ECP, MPO, and tryptase in effusion from 97 patients.(Tables 2,3)[6] Thirty-six pre-school children (age 14 months to 6 years), 41 children of school age (6-18 years), and 20 adults were selected in a consecutive, prospective manner [6]. All had documented hearing loss, flat tympanograms, and effusion of a minimum of 3 months duration unresponsive to antibiotic and/ or decongestant therapy. Ear effusions were collected at the time patients underwent routine M&T [6] (Tables 2,3).

All patients over 6 years old had allergies. Both Gates, et al. [14] and Yellon, et al. [15] observed that older children typically tend to have more chronic OME, and need repeated myringotomy and tympanostomy.

In the initial stages of serous otitis, mast cells have been found in the lamina propria and the pars flaccida [16,17], and this is not a normal feature [12]. Both eosinophils and neutrophils are integral components in these secretions [17]. Clinical studies have shown that patients with OME have allergies that can be diagnosed by standardized intradermal (IDT) or skin prick testing (SPT) and in vitro testing [6]. When these allergies are properly treated, the patient’s effusion will resolve [8,10,11]. Adding IDT testing to SPT discovers 54% more allergens [18].

Methods

Effusion subjects

We also measured tryptase and ECP in middle ear effusions from 38 individuals (i.e., 44 ears, including 6 pairs) who presented with refractory OME to a solo community-based otolaryngologist [17]. Subjects included 18 children (age 32 months to 6 years) and 15 children of school age (6-18 years) selected in a random, prospective manner. Five adults (age 55 to 69) with eustachian tube dysfunction served as controls (Table 4). Among the 33 diseased patients were several children with no known antecedent infections who presented after failing a school hearing test [17].

A second cohort of five children with 8 diseased ears (ages 5.2 to 16 years) was selected randomly for biopsy. All 5 patients had serum ELISA testing. Four other patients who had no signs of effusion or infection but were undergoing routine tympanoplasty for dry perforations served as controls. Biopsies from both normal and diseased patients were taken from the promontory of the middle ear following approval of the Franklin Memorial Hospital (Farmington, Maine) Committee on Ethics and Human Experimentation and with patient or parental consent. Working through the myringotomy incision, a 2 mm diameter sample of mucosa was removed using a microcup forceps (Figure 3) [17].

Intervention consisted of immunotherapy according to AAOA criteria. All patients in both treatment and control groups were found to be atopic. The sex, age, and number of tubes or adenoid surgeries in the two groups were compared (Table 5).

No statistical difference was found between the treatment and control cohorts for any parameter other than the apparent excess number of 51—70-year-olds in the treatment group.

Discussion

Diagnostic studies involving serum skin testing for allergy have shown little consistent results, partly due to the significant difference between intradermal (IDT) and skin prick testing (SPT), wherein the general allergists prefer SPT vs otolaryngologists (Figure 2) who prefer intradermal testing as being twice as sensitive [18].

Patients designated as having OME were those who maintained effusion beyond 2 months. The dilution of the effusion specimens in this study is an important consideration. Assuming an average volume of 0.3 mL of effusion diluted during collection with 2 mL of saline to wash the thick mucoid samples removed during M&T from the 20 French suction tube, the absolute tryptase concentration in those middle ears in which tryptase was measurable (mean 6.46 μg/l) was actually 6 to 7 times greater than that recorded and represents a mean of 38.8-45.2 μg/l. Mast cells were present in the mucosa [17] and submucosa in allergics but absent in controls.

To further characterize the relation of allergy or infection to OME, we measured ECP, MPO, and tryptase in effusion from an additional 97 patients [6]. Thirty-six children (age 14 months to 6 years), 41 children of school age (6-18 years), and 20 adults were selected in a consecutive, prospective manner. Ear effusions were collected at the time patients underwent routine M&T. Atopic Status: Eighty-one percent of this second group of 97 OME patients (79/97) were atopic [19]. Among the children, 93% (72/77) were atopic (Table 2) [6].

Mediator levels in effusions

The inflammatory response by eosinophils, neutrophils, and mast cells in the middle ear was distinctly different depending on the patient’s atopic status (p < 0.001). ECP was elevated (>10 μg/l) in 86.1% (68/79) of ears of atopic patients (mean 165.8 μg/L). Tryptase was elevated (mean 4.8 μg/L) in the effusion from 64% (23/36) of atopic patients. Tryptase was below 2 μg/L in all 7 non-atopic patients as well as in 1 PUR-OME and 12 atopic patients. There was no correlation of tryptase to either MPO or ECP (Spearman p > 0.05). The inflammatory response by eosinophils, neutrophils, and mast cells in the middle ear [6] was distinctly different depending on the patient’s atopic status (p < 0.001).

Efficacy of immunotherapy for atopic disease

Sporadic reports of the therapeutic efficacy of IT for OME have lacked documented controls until recently. In a study of 89 patients [17] aged 4 to 70 years with intractable middle ear disease who presented with chronic effusion or chronic draining perforations or tubes, all proved to be atopic by intradermal skin testing. All were offered allergy IT based on the results of their intradermal testing. A total of 21 individuals self-selected to be a “control cohort” by choosing not to proceed with IT for a variety of reasons. Specific allergy IT completely resolved 85% of 127 diseased ears and significantly improved an additional 5.5%. The condition in all children younger than 15 years and most adults resolved within 4 months, and they remained free of disease while on allergy IT for 2 to 8 years of follow-up. None of the controls’ 39 ears resolved spontaneously (p < .001) (Table 2) [6]. Most (85.7%) patients were pan-allergic to an average of 9 allergens, including dust (94%), animals (47%), ragweed (67%), and molds (88%). Nine were allergic only to seasonal pollens. A similar number of patients in both groups also had associated allergy symptoms at the time of presentation, including asthma (21%, 13%) and allergic rhinitis (63%, 53%). Importantly, over a third in both groups (37%, 48%) presented with otitis as their only allergic symptom. Surprisingly, allergic otitis presented as unilateral disease in 13%. Most, 108 of 127(85.0%) ears became and remained free of effusion or drainage within a year on IT.

Bias

Study limitations: There were several study limitations. First, the study was neither randomized nor blinded, so it has a risk of bias, and the two control groups were self-selected. Second, although 40% (39/97) of our patients had been skin tested by both methods, the absence of actual SPT testing due to the procedures of the specific practice studied did not allow for a direct comparison between SPT and IDT sensitivity among the other 60 patients. Third, none of the patients had an ET endoscopy. However, of the 9 adult failures, average age 53, 5 were sent for ET evaluation, and none were found to be candidates for ET dilatation.

Results

All patients in both treatment and control groups were found to be atopic. The sex, age, and number of tubes or adenoid surgeries in the two groups were compared (Table 2) [6]. The mean number of sets of tubes, including those inserted during the study, was similar in the two groups (2.58, 2.40).

The average patient with OME proved to be sensitive to 9 allergens (range 4–15). This study documented that in a select population, anti-allergy therapy is efficacious in preventing or limiting the duration of OME [17]. Immunotherapy is efficacious in preventing or limiting the duration of OME when comparing treatment patients to a control cohort.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first to our knowledge to document that, in a select population, anti-allergy therapy is efficacious in preventing or limiting the duration of OME while comparing treatment patients to a control cohort.

Our observations add to the body of evidence demonstrating that the cells and cytokines essential to the production of an immune-mediated hypersensitivity reaction (atopy) are present in the majority of ears that have chronic effusion. Neither tryptase nor ECP levels were elevated if the patient was not atopic (Table 2) [6].

Immunohistochemical staining of biopsy material from normal ears showed no evidence of either mast cells or eosinophils, but did demonstrate both cells to be present within the mucosa of 80% of ears from atopic children with OME [18].

The inflammatory response by eosinophils, neutrophils, and mast cells in the middle ear is distinctly different between atopic and non-atopic patients (p < 0.001) [17,19]. These findings provide further evidence that eosinophils and mast cells, both essential to a Th-2 driven immune response, are active in the majority of ears from atopics with chronic OME and support the hypothesis that: middle ear mucosa, similar to that of the rest of the upper respiratory tract, is capable of an allergic response [20-22]. Unlike the use of antibiotics, which only treat the current episode, when their allergies were properly treated with immunotherapy, the patient’s tendency to experience recurrent effusions all resolved.

Implications

This study documents that in a select population, anti-allergy therapy is efficacious in preventing or limiting the duration of OME while comparing treatment patients to a control cohort. Direct proof that allergy contributes to chronic OME and/or other manifestations of chronic middle-ear disease is best done by a randomized, DBPC trial. None have been published. Specific allergy immunotherapy significantly improved 5.5% and completely resolved 85% of 127 chronic otitis OME in these diseased ears. All children <15 and most adults resolved within 4 months and have remained free of disease while on allergy IT for 2 or more years of follow-up. None of the controls resolved spontaneously (p < 0.001).

The surprising finding that 85% of patients in this study were atopic by objective testing implies selection bias. This is more likely a result of the marked increase in sensitivity of IDT vs. either prick (sensitivity <45%) or RAST testing [6,22], especially in patients with low total IgE levels. It is for this reason that practice parameters of the AAAAI [22] and AAOA [23] suggest that, in the face of a negative prick test, intradermal testing may be the only practical way to determine sensitivity (Figure 2) [18]. The concern of a false positive IDT resulting from this increased sensitivity was addressed by requiring two positive tests. The average OME patient proved to be sensitive to nine allergens (range 4-15).

Take away

This work supports previous suggestions that the middle ear may serve as a target organ for allergic reactions [6,24-26] in that patients with OME were almost universally atopic and resolved with immunotherapy. Medical evidence supports the link between allergy and OME. The middle ear behaves like the rest of the respiratory tract, and what has been learned about the atopic response in the sinuses and lungs may be applied to the study of the middle ear to help in understanding OME. Histologic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies based on objective allergy testing (Table 1) [4] have thus far (1) established that the majority of patients with OME are atopic, and (2) demonstrated that all the mediators necessary for a Th2 allergic response are present in the middle ear (Table 3) [6].

This data suggests that many patients with intractable, refractory middle-ear disease appear to be atopic and deserve consideration for an aggressive allergy evaluation, as immunotherapy offers the best opportunity for and the most long-lasting resolution of OME [4,6,8].

Permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted material from other sources, including the Web.

Specific appreciation to Dr. John Benziger and Bill Nurse, Franklin Memorial Hospital, Farmington, Maine, for preparing the biopsy material, and to Mrs. Ilona Jones at Pharmacia & Upjohn Diagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden, for measuring tryptase. And a special thank you to Dr. Melissa Weekley for reviewing and commenting on this paper.

- Graydon K, Waterworth C, Miller H, Gunasekera H. Global burden of hearing impairment and ear disease. J Laryngol Otol. 2019;133(1):18–25. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022215118001275

- Gates G, Avery C, Prihoda T, Holt GR. Delayed onset post-tympanotomy otorrhea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;98(1):111–5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/019459988809800203

- Williams R, Chaimers T, Stange K, Chalmers FT, Bowlin SJ. Use of antibiotics in preventing recurrent acute otitis media and in treating otitis media with effusion. JAMA. 1993;270(11):1344–51. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8141875/

- Hurst DS, Denne CM. The relation of allergy to Eustachian tube dysfunction and the subsequent need for insertion of pressure equalization tubes. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020:39–47. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561320918805

- Teele D, Pelton S, Kline J. Bacteriology of acute otitis media unresponsive to initial antimicrobial therapy. J Pediatr. 1981;98(2):537–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80755-x

- Hurst DS, Venge P. Evidence of eosinophil, neutrophil, and mast-cell mediators in the effusion of OME patients with and without atopy. Allergy. 2000;55:435–41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00289.x

- Hurst DS, McDaniel AB. Clinical relevance and advantages of intradermal test results in 371 patients with allergic rhinitis, asthma, and/or otitis media with effusion. Cells. 2021;10(11):3224. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113224

- Bousquet J, Michel FB. In vivo methods for the study of allergy: skin tests. In: Middleton E Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, Adkinson NF Jr, Yunginger JW, editors. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby Co.; 1995;573–94.

- Bikhazi P, Ryan AF. Expression of immunoregulatory cytokines during acute and chronic middle ear immune response. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:629–34. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-199506000-00013

- McMahan JT, Calenoff E, Croft J. Chronic otitis media with effusion and allergy: Modified RAST analysis of 119 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:427–31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/019459988108900315

- Hurst DS. Allergy management of refractory otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;102:664–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/019459989010200607

- Berger G, Hawke M, Ekem JK. Mast cells in human middle ear mucosa in health and disease. J Otolaryngol. 1984;13:370–4. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6085806/

- Nsouli TM, Nsouli SM, Linde RE. The role of food allergy in serous otitis media. Ann Allergy. 1994;73:215–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8092554/

- Berger G, Hawke M, Ekem JK. Bone resorption in chronic otitis media: the role of mast cells. Acta Otolaryngol. 1985;100:72–80. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/00016488509108590

- Yellon RF, Leonard G, Marucha P. Characterization of cytokines present in middle ear effusions. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:165–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-199102000-00011

- Lim DJ. Functional morphology of the lining membrane of the middle ear and Eustachian tube. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1974;83 Suppl 11:5–26. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489474083s1102

- Hurst DS, Amin K, Sevéus L, Venge P. Evidence of mast cell activity in the middle ears of children with otitis media with effusion. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:471–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-199903000-00024

- Hurst DS, Gordon BR, McDaniel AB, Poe DS. Intradermal testing doubles identification of allergy among 110 immunotherapy-responsive patients with Eustachian tube dysfunction. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(5):763. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11050763

- Hurst DS, Venge P. Levels of eosinophil cationic protein and myeloperoxidase from chronic middle ear effusion in patients with allergy and/or acute infection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:531–44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0194-5998(96)70244-9

- Hurst DS. The association of otitis media with effusion and allergy as demonstrated by intradermal skin testing and eosinophil cationic protein levels in both middle ear effusions and mucosal biopsies. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:1128–37. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-199609000-00017

- Hellstrom S, Salen B, Stenfors LE. The site of initial production and transport of effusion materials in otitis media serosa. Acta Otolaryngol. 1982;93:435–40. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/00016488209130901

- Chinoy E, Yee SL, Bahna SL. Skin testing versus radioallergosorbent testing for indoor allergens. Clin Mol Allergy. 2005;3(1):4. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-7961-3-4

- King HC. An otolaryngologist’s guide to allergy. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1990. Available from: https://elib.must.ac.ug/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=4444

- Hurst DS. Efficacy of allergy immunotherapy as a treatment for patients with chronic otitis media with effusion. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(8):1215–23. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.04.013

- Hall L, Lukat RM. Results of allergy treatment on the Eustachian tube in chronic serous otitis media. Am J Otol. 1981;3:116–21. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7197884/

- Palva T, Johnsson L. Findings in a pair of temporal bones from a patient with secretory otitis media and chronic middle ear infection. Acta Otolaryngol. 1984;98:208–20. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3109/00016488409107557

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley